India’s independence is celebrated every year as the triumph of a civilization that broke colonial chains and chose democracy, equality, and dignity as its guiding principles. Yet, beneath this story of victory lies another unfinished journey – that of communities who, even after more than 75 years of freedom, are still waiting to experience the true meaning of independence.

These are the Denotified, Nomadic, and Semi-Nomadic Tribes, known today as DNT, NT, and SNT communities. Their history is filled with extraordinary contributions to the country, yet they have remained strikingly neglected by governance systems. On 31 August 1952, the Parliament of India repealed the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, a dark legacy of colonial rule that had formally branded nearly two hundred communities as “criminal tribes.” By birth alone, men, women, and children were stigmatized as criminals, denied education, land, and opportunities for livelihood.

Although independent India “denotified” these communities by repealing the Act, the shadow of stigma lingered. August 31 came to be marked as Mukti Divas – a day symbolizing freedom from colonial chains, but also a reminder of the unfinished struggle for dignity and justice.

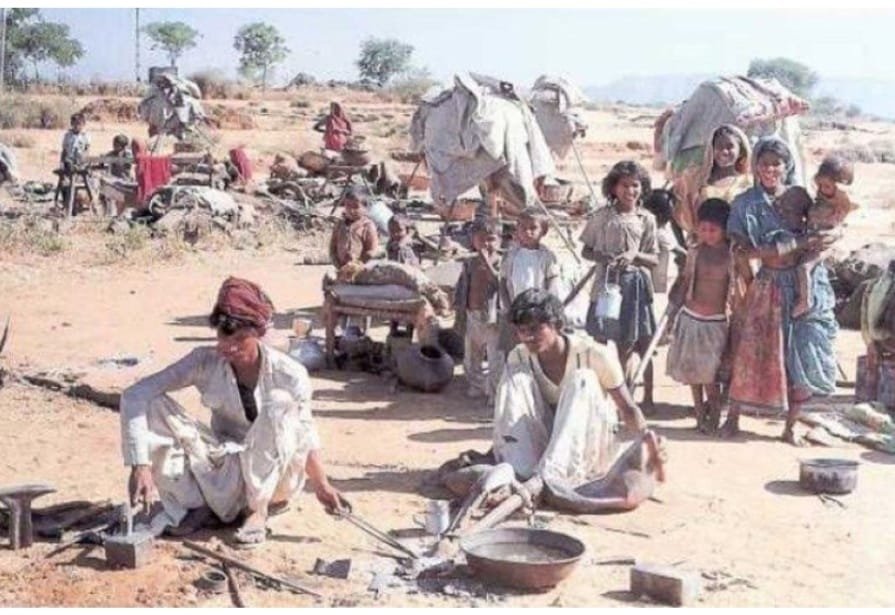

The tragedy of this colonial label was that it ignored the immense cultural and economic contributions of these communities. For centuries, nomadic groups sustained the rural economy through pastoralism, blacksmithing, carpentry, stonework, pottery, folk arts, daring performances, and entertainment. Communities such as the Nat, Banjara, Kanjar, Sansi, Vaghri, Sikligar, Gadaliya Lohar, Gujjar, and Mall were recognized not only for their labor and creativity but also for their resilience in adversity. Many of them bravely supported India’s freedom struggle, sheltering revolutionaries, carrying messages, and even sacrificing their lives against colonial repression.

Yet while other freedom fighters were honored as national heroes, these communities were punished twice – first by colonial oppression, and later by being erased from history. Their immense role in shaping India’s culture, economy, and independence has remained largely invisible.

The repeal of the Criminal Tribes Act in 1952 was expected to mark a new dawn, but soon new troubles emerged. Several states introduced Habitual Offenders Acts, which in practice carried forward the same machinery of suspicion and surveillance. Entire communities continued to be treated as potential criminals, recorded in police registers, subjected to midnight raids, and harassed by bureaucracy. The legal “denotification” did not translate into social or economic freedom. Discrimination only deepened their marginalization, pushing them to the edges of villages and towns, where access to education, housing, and livelihoods remained a distant dream.

In October 2024, the Supreme Court of India declared the Habitual Offenders laws “constitutionally suspect” and pointed to their misuse, particularly against denotified tribes. These laws are direct descendants of the colonial-era Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 that should have vanished with independence but remain in force in 14 states and union territories even today. The National Human Rights Commission in 2000, the Prof. Virginius Xaxa Committee in 2014, and the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in 2007 all recommended their repeal. Their persistence is a stain on democracy, equality, and dignity. It is time for the Government of India to act decisively, abolish these laws fully, and end the historical injustice against DNT, NT, and SNT communities while upholding the constitutional promise of justice and dignity.

Their struggles have been further complicated by cycles of forced displacement in independent India. With little land and almost no education, thousands of DNT, NT, and SNT families moved to cities in search of livelihood. They built temporary huts on the margins of towns, working as daily wage laborers, construction workers, roadside vendors, and performers. Over decades, as cities expanded, these very settlements turned into valuable real estate. Developers and urban authorities, eager to exploit the land, evicted families who had lived there for generations. Without formal land records, families had little legal protection and were rendered homeless without alternatives, forced once again into wandering. This cycle of displacement continues today, disrupting livelihoods and children’s education, while urban skylines rise on the same ground where these families once lived.

Among all the challenges, the education gap is the most alarming. Compared to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and OBCs, the DNT, NT, and SNT communities remain nearly a century behind in literacy and educational access. This is not just a matter of statistics but a generational impact of being deprived of education due to hostile conditions and daily struggles for survival. The absence of education has made dignified employment nearly impossible, locking many families into cycles of labor and exploitation. The problem is made worse by the fact that only six states issue DNT, NT, and SNT certificates, and even there the process is highly bureaucratic and discouraging, excluding most people from welfare benefits. This administrative exclusion has further betrayed the constitutional promise of equality.

Yet, this story is not only one of despair. In recent years, there have been positive steps that deserve recognition. The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment launched the SEED scheme, focused on education, health, livelihood, and housing. In a short span, the scheme has reached eight states, forming nearly five thousand women’s self-help groups, creating networks of self-employment and mutual support. Thousands of families have benefited from education assistance and health programs. More than twenty NGOs have helped implement the scheme on the ground, proving that when the state and civil society collaborate, progress is possible.

But considering the widespread deprivation faced by 1,262 communities across India, these efforts are only a beginning. This urgency for systemic reform echoed nationally on 30 July 2025, when the DNT Development Foundation organized a national conference in Delhi with more than 220 representatives from 16 states. It was not only a platform to remember past struggles but also an opportunity to set the course ahead. Issues of education, housing, migration, livelihoods, and social stigma were discussed with clarity.

The very fact that such a national conference was held shows the rising awareness and unity within these communities. The tireless efforts of Bharatbhai Patni and Praveen Ghuge, members of the DWBDNC, have been instrumental in bringing national attention to their welfare and development. Importantly, the conference also drew the attention of policymakers. Only days later, on 11 August 2025, BJP MP Dr. K. Laxman raised these issues in the Rajya Sabha. He praised the achievements of the SEED scheme, highlighted the ongoing challenges faced by DNT, NT, and SNT communities, and urged two critical measures. First, he suggested that the upcoming Census should include a separate column for DNT, NT, and SNT communities alongside caste names, which is vital for accurate data and targeted policy. Second, he reiterated a key recommendation of the Idate Commission – the establishment of a permanent National Commission for DNT, NT, and SNT communities. Such a body would provide institutional strength, accountability, and a voice for communities long invisible in governance structures.

Nearly ten percent of India’s population belongs to these communities. This means that one in every ten Indians carries the burden of this unjust legacy, even as they contribute to the economy in countless ways. They are the laborers building our cities, the pastoralists who supply milk, the artists preserving folk traditions, and the workers keeping industries alive. Their contributions cannot be denied, yet they remain unrecognized. These are resilient, self-reliant people who, despite minimal state support, survive some of the harshest conditions. Their patriotism, faith in Indian democracy, and deep attachment to culture and faith remain unbroken, even when justice has often failed them.

Mukti Divas is therefore not just a symbolic date on the calendar. It is a reminder of promises still unfulfilled and possibilities yet to be realized. It reminds us that despite being once branded “born criminals,” these communities never abandoned their loyalty to the nation. They endured discrimination, economic hardship, and social exclusion, but they did not lose patience or sever their ties with the land of their ancestors. Instead, they continued to demand their rightful place in their own country.

In 2025, Mukti Divas was celebrated across the nation with great spirit, encouraged by the government’s active role. It is important that this day be commemorated every year not only to honor history but also to educate future generations about injustices that must never be repeated. The unfinished dream of India’s DNT, NT, and SNT communities is not theirs alone. It is the nation’s unfinished dream.

The true test of democracy is not merely in celebrating freedoms already won but in ensuring they reach those who have been left behind. The government’s initiatives like SEED are commendable, but what is now required is bold and systemic reform. The Census must include a separate column for DNT, NT, and SNT communities to ensure accurate data. A permanent National Commission should be created to safeguard their rights. Nationwide housing and land rights programs should be launched to prevent forced displacement. And most importantly, determined efforts must be made to bring education to every child. Only then will Mukti Divas stand not merely for freedom from colonial laws but also for liberation from stigma, exclusion, and poverty imposed on these communities.

It is time to recognize that DNT, NT, and SNT communities are not relics of a tragic past but essential contributors to India’s present and future. Their freedom is our freedom, their dignity is our dignity, and their progress is inseparable from the progress of the nation. Mukti Divas reminds us that independence is complete only when it belongs to all.

Leave a Reply to Mali Ishwarbhai Budhabhai Cancel reply